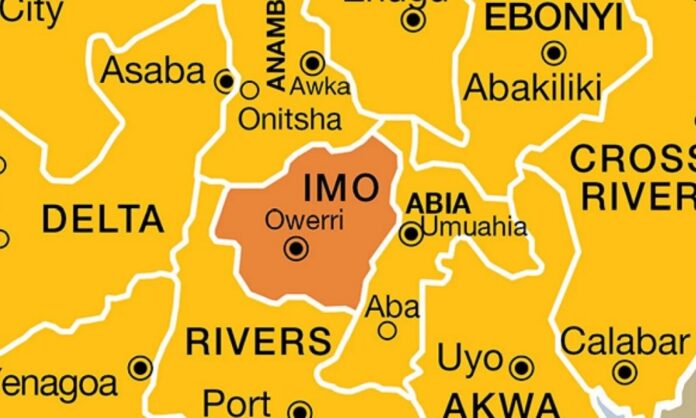

The well attended Imo Economic Summit may have come and gone but the new economic posers it threw up and the new investment realities it exposed will for a long time dominate economic discourse at different fora.

While some aligned with the conversation as held, others generated a fresh argument/position for local infrastructure, community engagement, and investor-friendly reforms.

Among these varying voices from Nigerians of good will, the most cerebral and of course the loudest came from Nnenna Bridget Amuji, a well foresighted and quietly influential United States based economic researcher and financial analyst. Aside from propagating solutions to critical challenges bedevilling Nigeria and the subregion, this piece is of the views that her position holds a pathway to sustainable economic growth and development – a position that makes it compelling and must read for the nation’s economic handlers, policymakers, development professionals and critical stakeholders.

The referenced position reads: “The just-concluded Imo State Economic Summit rightly spotlighted natural gas as a cornerstone of Nigeria’s and Africa’s economic future. With vast reserves, gas is heralded as the “transition fuel” that will power industries, generate electricity, and fuel export revenues. However, for the financial analyst, global investor, or policymaker, long-term profitability is not guaranteed by reserves alone. It is determined by meticulously navigating a complex web of regulatory and market risks. The summit’s dialogue provides a crucial springboard for this clear-eyed assessment.

The Promise: A Trifecta of Global Demand. The profitability thesis rests on a powerful trio of demands, demonstrating the strategic global importance of African gas.

Domestic Energy Poverty: With over 600 million Africans lacking electricity, gas offers a reliable baseload to unlock industrialization and human capital development.

Global Energy Security: The European pivot from Russian gas has created an urgent, albeit potentially finite, window for Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) exports, positioning Africa as a vital geo-political energy supplier.

Regional Integration: Projects like the Nigeria-Morocco Gas Pipeline underscore a growing market within Africa itself, promising more stable, predictable regional demand.

The Peril: Navigating the Risk Matrix as a Financial Analyst.

“The Imo discussions highlighted that capitalising on this promise requires meticulously managing key risks. From a financial analyst’s perspective, these are the four non-negotiable risk categories that dictate project viability:

Regulatory Instability & Policy Whiplash: Regulatory instability remains the single greatest deterrent to long-term gas investment in Africa, and the summit’s call for “investment-friendly frameworks” will only carry weight if it translates into durable, legally anchored policy. Investors in large-scale gas infrastructure require predictable fiscal terms, clear ownership structures, and a transparent regulatory pathway from exploration through to export. Africa’s recent experience demonstrates the cost of policy whiplash; in Nigeria, repeated delays and revisions to the Petroleum Industry Bill created uncertainty around gas pricing, taxation, and domestic supply obligations, slowing progress on projects such as NLNG expansion and upstream gas developments. Tanzania’s offshore LNG ambitions stalled when new legislation abruptly altered contract terms and revenue expectations, forcing lenders to reassess long-term risk. In Mozambique, periods of tightening around local content rules and state participation created hesitation among developers as they sought firmer legal assurances before committing to multi-billion-dollar infrastructure. These cases show how sudden changes in taxes, royalties, or regulatory obligations can render even the most promising gas projects unbankable, underscoring the need for stable, credible, and consistently applied policy regimes.

“The “Energy Transition” Capital Discount: Global trends in climate policy, ESG finance standards, and security/human-rights scrutiny are increasingly imposing what can be described as an “energy-transition capital discount” on major African gas projects. For instance, the Mozambique LNG project, once backed by export-credit agencies from the UK and the Netherlands, recently lost a combined US $2.2 billion in financing when both UK Export Finance (UKEF) and Atradius Dutch State Business withdrew their commitments, citing increased risks, including environmental, human-rights and security concerns. Similarly, Crédit Agricole has publicly declared that it will not finance certain new LNG projects, including the Rovuma LNG development, reflecting a broader repositioning of European lenders away from new fossil-fuel ventures under ESG pressure.

“As a result, even projects that remain technically and commercially viable must now contend with higher financing costs, longer negotiation periods, and additional requirements (e.g., climate-alignment assessments, methane-leakage mitigation plans, enhanced human-rights compliance). The implication is clear: African gas projects can only remain bankable if they credibly align with a “just transition” narrative demonstrating that they support the continent’s development and energy-security needs while meeting rising global climate and ESG standards rather than being penalised by a one-size-fits-all aversion to fossil fuels.

“Infrastructure Deficit & Value Erosion: Infrastructure deficits along the gas value chain continue to erode potential profits in Africa, as the distance between the wellhead and market creates both economic and environmental costs. In Nigeria, the World Bank notes that “billions of cubic metres of associated gas are flared each year, representing lost revenue and unnecessary CO₂ emissions” due to inadequate pipeline, processing, and commercial offtake capacity. Similarly, Ghana’s Energy Commission reports that “gas supply constraints have repeatedly forced thermal power plants to reduce generation, leading to foregone electricity production and economic losses.” In Angola, the International Energy Agency highlights that “historically high flaring rates reflect underutilised midstream infrastructure and limited pipeline capacity, resulting in lost commercial gas.” These cases demonstrate that massive, coordinated investment in midstream infrastructure, particularly through public-private partnerships, is non-negotiable to prevent value erosion, reduce environmental impact, and enable Africa’s gas resources to reach markets efficiently.

“Geo-Economic Volatility: African gas projects operate in a highly competitive and volatile global market, where external supply shocks can rapidly undermine profitability. The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis notes that “a global surge in liquefaction capacity, primarily outside Africa, threatens to produce a glut that could depress LNG prices, undermining the economics of delayed African projects.” Similarly, market analysts highlight that “U.S. LNG output and new global liquefaction facilities may tip the market into oversupply by 2026–2030, pressuring spot and contract prices downward” and raising the stakes for securing long-term offtake agreements. The International Energy Agency further observes that “slower-than-expected, demand growth combined with rising supply exposes export-oriented infrastructure to underutilization and depressed returns.” Together, these dynamics underscore that African gas projects must lock in buyers through credible long-term contracts, maintain cost-competitiveness, and minimise bureaucratic and security-related delays; without these measures, breakeven prices can rise above market realisable prices, leaving projects vulnerable to the volatility of the global LNG market.

“The Execution Mandate: From Reserves to Resilience.

The Imo State Economic Summit’s most potent contribution is shifting the conversation from mere resource extraction to integrated economic development.

“As a financial economist, it is clear that the most profitable African gas projects will not be those that simply maximise export volumes, but those that are strategically de-risked, socially integrated, and regionally aligned.

“Anchor Domestic Value Chains: Africa’s gas potential can generate exponentially higher value when it fuels local industrialization. By supplying domestic industries such as fertilizer production, steel, and light manufacturing, projects can capture economic value before export, mitigating the traditional infrastructure deficit and value erosion caused by flaring and limited midstream capacity. The Imo Economic Summit highlighted this principle locally, with the state government emphasizing public-private partnerships to build pipelines, processing hubs, and power-to-industry links that ensure gas reaches domestic industrial users before export. Integration into domestic value chains aligns with AFCFTA objectives, enabling industrial outputs to circulate regionally, creating economic resilience, and strengthening Africa’s collective energy security. Regional frameworks like AFREC and national policies such as Nigeria’s Gas Masterplan provide structured pathways to link gas production with industrial hubs, reducing investment risk.

“Finance the Future: Long-term profitability also requires hedging against global market volatility and ESG-related capital constraints. Revenues from gas can be structured to fund sovereign wealth funds and invest in renewable energy infrastructure, enhancing resilience to price shocks and financing Africa’s energy transition. African projects that incorporate low-methane LNG practices, gas-to-power schemes that stabilize grids for solar and wind, and regional cooperation through frameworks like Agenda 2063 reduce the “energy transition capital discount” imposed by global financiers. Locally, Imo’s focus on infrastructure development and regulatory certainty signals to investors that gas projects can be bankable while aligned with domestic and regional transition goals.

“Operate with Social License: Finally, African gas projects must address regulatory instability and community risk. Engaging host communities as equity partners and providing tangible benefits jobs, infrastructure, and electricity access, mitigates operational risks linked to unrest or policy whiplash. The Imo Economic Summit explicitly recognized this, pledging mechanisms to ensure communities share in industrial benefits, thereby de-risking projects from social and political disruptions. Consistent adherence to national frameworks on local content, gas commercialization, and community engagement further stabilizes the investment climate.

“The due diligence checklist for African natural gas must now weigh regulatory coherence, social integration, and alignment with domestic and regional industrial objectives as heavily as geological surveys. The projects that will deliver sustainable, long-term returns are those embedded in a stable policy environment, designed to capture value through domestic industrialization, resilient to global market volatility, and built for a decarbonizing world. The Imo Economic Summit has set a clear agenda for local infrastructure, community engagement, and investor-friendly reforms; now, the hard work of execution begins to transform geological wealth into enduring financial returns, regional industrial value, and tangible social benefit. By leveraging frameworks such as AFCFTA, AFREC, and Agenda 2063, African gas projects can achieve not just profitability, but strategic, continent-wide impact.

”Utomi, a Media Specialist writes from Lagos, Nigeria.