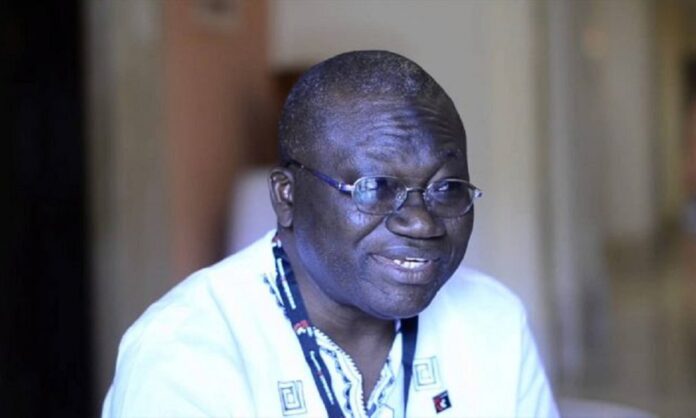

2025 marks the 20th anniversary of the passing of Michael Athokhamien Omnibus Imoudu (Pa Imoudu) , globally acknowledged as Nigeria’s NO 1 labour leader and activist. Pa Imoudu lived between 7 September 1902 (when he was born at Sabongida Ora, Owan West Local Government Area of Edo state) and 22 June 2005. He died at 103 years.

Assuming there is any theory or practices of unionism and unionists known as Imouduism, one significant variant of it must deal with longevity. At 103 on earth, Pa Michael Aithokhaimien Imoudu upturned conventional wisdom about what actually promotes long life. The labour icon astonishingly combined stress, tension, agitation, deprivation, and harassment that characterised his historic union life, with a century-long life. Imoudu’s longevity proved an exception to the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) typical report that often puts Nigeria’s life expectancy at 50. Pundits on struggling life definitely have a lot to reflect on Imoudu’s life. Himself an ideologue of Maoist learning, Imoudu outlived Chairman Mao (82) and even his older successor, Deng Xiaoping (92). A convinced and proud Zikist (the first Nigeria Labour Congress (NLC) under his leadership in 1950, amidst controversy, affiliated to Zik’s NCNC), Imoudu nonetheless outlived Zik! In 1987, he attended the funeral of Chief Obafemi Awolowo, his later years’ benefactor, without extra support other than his legendary walking stick. What has age then got to do with some iconic men and women whose vocation is service to humanity? We all

know that some men and women with a deep impact on mankind often live shortened lives. But why do some of the world’s struggling men turn some exceptions? Why do they not fall easy prey to those common afflictions that have shortened the lives of even the most affluent and comfortable that lay no claim to any greater human cause? Imoudu’s life particularly assumes a mystique, given that his notable contemporaries and comrades in the trade union movement have long passed on before him. Witness, Alhaji H.P. Adebola, Gogo Nzeribe, Simeon Adebo, Wahab Goodluck, Odeyemi, Adio Moses, Armstrong Ogbona, Mpamugo, to mention but few. Pa Imoudu truly stands out as the mystery comrade, a senior ‘Abami-Eda’ of the trade union movement.

If longevity is an issue in Imouduism, unprecedented honesty of purpose and commitment to the road freely chosen is another variant of it. The road chosen leads to the restoration of the dignity of labour and upliftment of working men from the deprivations of wage-slavery, particularly under colonialism. This honesty of purpose explains the exemplary spirit of self-sacrifice, spontaneity, firmness, courage and even naivety that were traits of Imoudu’s active years. A scholar of Nigeria’s labour history, Roger Grail (1985), once observed that since the early 30s, when he challenged the absolute colonial labour regime in a strike, Imoudu became the “bete noire” of the colonial government, adding that no other employee in Nigeria had more queries in his file. Imoudu intermittently went in and out of prisons and ended up indeed as a dismissed staff of the Nigerian Railway without a pension! Very few trade unionists have demonstrated this sense of exceptional commitment since Imoudu’s days.

There are weighty objective conditions that will always limit the actions of those who desire some changes in society. Imouduism, however, shows that the potentials always exist for those concerned men and women to act in ways and manners in which changes are inevitable. The existing order may not be altered, but it can be modified for the better. Imouduism emerged during the depression/inter-war years of (1919-1939). Starvation wages and casual labour, and ‘king-kong’, industrial relations were the norms. Unions’ functionaries were criminalised while the British colonial managers encouraged discriminatory, racist labour practices. Imoudu belonged to the first generation of Nigerian workers’ force. Together with his compatriots, they came into confrontation with the colonial order. The tactics and strategies were as diverse as the problems; strikes, rallies, appeals and petition writings. The only thing constant in Imouduism was the purpose: to get justice for working men. It is to the eternal Imoudu’s credit that the early struggles of workers humbled colonial employees, making them reckon with labour and unions. The introduction of Cost of Living Allowance (COLA) (modern-day fringe benefits), abolition of casual labour, job-classification and minimum wage were the fallouts of the principled struggle of Imoudu’s era. The subsequent labour reforms, which made the government recognise trade unions through the famous trade union Ordinance of 1938, consciously provided official encouragement of enlightened union officials, strong and independent unions, mediation and conciliation in trade disputes, and workmen’s compensation legislation, were logical outcomes of Imouduism.

Imouduism was also about organisation, the obvious foundation for workers’ collective actions. In 1932, as a machinist, with other daily paid operatives and apprentices in Railway mechanical workshops, he formed the then Nigerian Railways workers’ union, disregarding the then existing National Staff Union and the Mechanic Union, which represented only the elitist clerical/technical and complement staff. Since then, Imoudu had been part of the formation of not less than 10 (ten) unions and labour centres. He could disagree on principles and walk out of the organisation, as was the case during the ideological acrimony of the 50s/60s, but only to form another organisation and not retreat to resignation. Common to all Imoudu-led organisations was independence and democratic methods. Imouduism was an epitome of active and worthy voluntarism in which unionists’ relevance was measurable only (and only!) in reference to workers’ interest and nothing more. As an organisation man, no restriction for Imouduism: started as an employee of Railways, Imoudu transformed into a full-time unionist spanning four decades. The artificial divide of “card/ non-card” carrying was alien to Imouduism. Again few unionists have been able to cross all trade union bridges as the legendary Imoudu.

Lastly, Imouduism threw up men from all humble backgrounds representing the great diversities of great Nigeria. They were primarily motivated by the need to serve humanity through a deep commitment to the workers’ union struggle and the struggle against British imperialism. They included great names like Nduka Eze, I.O. Elias, Gogo Nzeribe, Mallan Nock, Ikoro, Uche Onu, Kaltungo, H.P. Adebola, Simon Adebo, Etim Bassey, and Wahab Goodluck, among others. Thanks to their honesty of purpose and learning by action. The result was the laying of the foundation for one of the pillars of post-independence, namely, Nigeria’s trade union movement. Nigeria’s political parties actually learn from the wealth of experience generated by these pioneer unionists in organisation building, conduct of meetings and methods of strategy. It is significant to note that future leaders of post-independent Nigeria emerged from the ranks of these self-made men. The notables include late T. Elias, a member of the executive council of the Railway Native Staff union in 1919. He later became a Professor of Law and President of the World Court in The Hague. Then late Chief Simon Adebo. He was the secretary to the Federal Union of Railwaymen under Imoudu’s leadership. He later became secretary to the Western State Government and Nigeria’s Ambassador tothe United Nations.

Pa Imodu went further to transcend the limitation of trade unionism and its inherent “bread and butter demands” of legitimate wage improvements. Imoudu acted politically and even partisanship. In 1946, Imoudu unapologetically identified with the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC), Nigeria’s foremost nationalist political party, which between 1944 to 1966, fought for independence. Indeed, Imoudu was nominated to the executive council of the party. Together with Nnamdi Azikwe and

Herbert Macaulay was a member of the NCNC’s delegation to London protesting the 1946 colonial Richards Constitution.

He and his compatriots championed the formation of labour and socialist parties. He was famous for his quote; ( I am Nigeria’s Chairman Mao). In the Second Republic, he decidedly joined Mallam Aminu Kano’s Peoples Redemption Party (PRP), the centre party. When PRP split, Imoudu logically pitched tent with the more radical faction of the late Governors Balarabe Musa of Kaduna State and Abubakar Rimi of Kano State. Indeed, the faction was known as the Imoudu faction.

Following NLC’s demand, former Military President Babangida renamed the then National Institute for Labour Studies (NILS) (commissioned in 1983 by late President Shehu Shagari) Micheal Imoudu National Institute for Labour Studies ( MINILS). The mandate of the tripartite governed MINILS ( labour, government and employers) is the promotion of labour education in Nigeria and the West African sub-region. Imoudu is Dead! Long live Imoudusim!

Comrade Issa Aremu mni

Director General (Micheal Imoudu National Institute for Labour Studies ( MINILS). ILORIN.