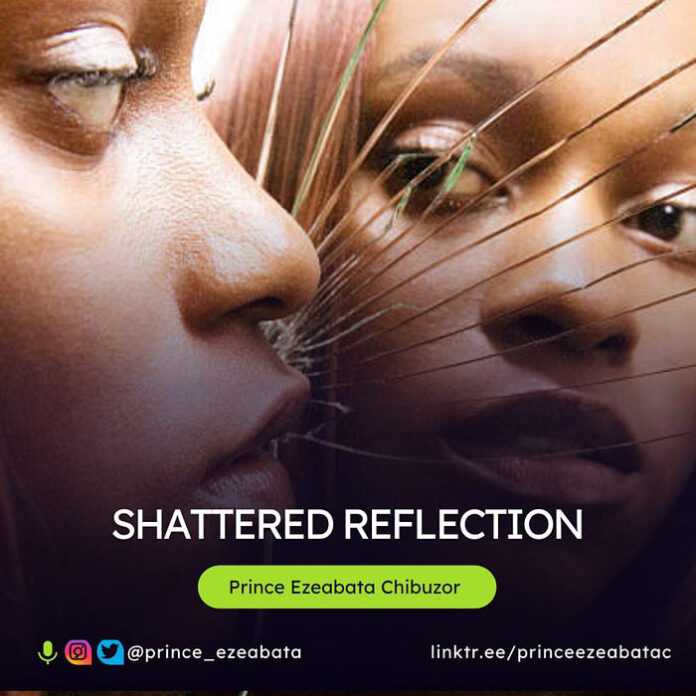

This is a work of fiction. It is however a similitude to live events, and witnesses. Read, and grasp the subtle lessons therein.

She is dead. She died yesterday. She drowned in the pool of her own blood. No one saw this coming, because just two months ago, she uploaded his picture on her WhatsApp status. “My ride or die. I can kill for you” was the caption. When she posted his picture, she had just arrived from her birthday party. He had bought her a bouquet of roses — blood red with stems trimmed short, just as she preferred — and a pair of silver shoes that caught the light in ways that made her feel, briefly, like she was worth being seen. Just as she loved, he put up a show, and everything went as perfectly as the script he’d written for them both.

She met him exactly five years ago. She was 24. Just out of university with a second-class upper degree that felt hollow in her hands. She was serving in one of those states where they speak Pidgin English as lingua franca and eat a lot of fish for dinner — , with its waterways and oil rigs punctuating the landscape like reluctant guests.

When she met him, he was fresh out of service himself, and just toggling between two freelancing jobs — graphic design and content writing. His fingers were always calloused from hours on the keyboard. Those hands would later trace the outline of her collarbone in ways that made her forget, temporarily, that she had been taught she wasn’t deserving of gentle touches.

“You have eyes like deep wells,” he told her that first evening at her PPA, the generator humming in the background, casting shadows that danced across the veranda. “A man could drown in them if he is not careful.”

She looked away, the compliment landing like a foreign object in her chest. “My father says they’re too big. Like a neighbor’s dog.”

“Your father doesn’t understand art,” he replied, not missing a beat. “Those eyes see things others don’t. I can tell.”

She was somewhat hard to please, her walls built high from years of dismissal and subtle cruelty. But she fell for his wit and sense of humor — the way he could navigate a conversation like a skilled sailor, knowing exactly when to tack and when to let the wind carry them. He was a collected young man who had earned an unspoken degree in keyboard flirting. So when they began to text, it wasn’t long before he struck a chord, and another chord, playing her vulnerability like an instrument he had studied all his life.

She grew up longing for the attention and genuine love of her parents, particularly her father. Her household in one of those cities was immaculate, with polished wooden furniture and perfectly arranged family photos that told lies about their dynamic — mother, father, daughter, all smiling under the photographer’s instruction to “look happy, look like a family.” Her father, a secondary school principal with breathe perpetually soured by beer and disappointment, had wanted a son. Her mother, a nurse who worked night shifts missed her baby’s little wins during the day — because she was too tired, too sad, or just needed peace.

Neither parents got what they wanted — thus, she bore the weight of their disappointment.

“Stand up straight,” her father would bark at dinner. “Your shoulders slump like you’re carrying the world. Nobody wants a wife who looks defeated before the battle begins.”

“Yes, Papa,” she would reply, straightening her spine until it ached, trying to occupy less space even as she made herself taller.

She thought herself not beautiful. She wasn’t short. She wasn’t tall either. She was of average height — five feet five inches of careful movements and calculated words. Her feet were tender, her limbs slim but without the curves that the boys at school whistled at. When she walked, she walked with a stumbling gait, a slight asymmetry from a childhood accident that her father never let her forget. Her gaze always screamed reserved and shy, eyes downcast as if perpetually searching for threats on the ground before her.

One event continually reminded her of how un-beautifully made she believed herself to be. While in a bid to please her mother, as she had been instructed to make a stew for Sunday dinner and serve her father, she accidentally knocked her foot against the edge of the iron door while carrying the hot plate of jollof rice. The tray slipped from her hands and fell to the floor, making that sharp, echoing noise that stainless steel makes when it meets ceramic tiles. The food splattered across the floor, grains of orange rice like fallen soldiers in a lost battle.

She stood fixed to the spot, absorbing the moment, before realizing she had sustained a cut on her big toe. The blood pooled under her foot, but the bleeding wasn’t her concern because when her mother came rushing in, her first words were: “Bad child. Devil’s seed.”

Her father’s word was final: “See her big eyes. You have very big eyes like our neighbor’s dog. That’s why you cannot see where you are going.”

That night, as she cleaned rice from between the tiles, she heard her father tell her mother: “This one will bring us nothing but shame. Who will marry a clumsy girl with eyes too large for her face? We should have tried for another after her.”

She was twelve then. By sixteen, she had perfected the art of silent crying, tears that fell without sound or facial movement. By twenty, she had stopped crying altogether, the well of her tears seemingly dried up from overuse.

Although she had grown into a woman with a university degree and a job, she was constantly reminded that she was a good-for-nothing girl with large, bulging eyes whom no man would choose to marry. To crown it all, she had an awkward gait, which she never even knew she had until a boy in secondary school mimicked her walk to the amusement of their classmates.

“The limping beauty,” they called her, the nickname sticking like gum under a desk.

When he met her, he soon figured out her weaknesses and capitalized on them to woo her. He was a pro in keyboard flirting, so when he settled down to praise her looks, her eyes, her subtle curves, and her voice, she melted. She melted not necessarily because she felt she was beautiful, but because he made her believe his words to be true.

“Your eyes,” he would text late at night when she was most vulnerable, the blue light of her phone screen illuminating her face in the darkness of her room, “they’re like windows to a soul that’s seen too much pain and still chooses kindness. Do you know how rare that is, Babe?”

He made her grow attached to him. He made her trust him. He made her settle with him. To her, he was everything. She had nothing — no God, no purpose, no esteem, no self-love — but him. He made her feel the love she had never experienced. He made her feel special in a way she had never felt before.

“I want to be your girl,” she told him one evening after he had cooked for her — a simple meal of plantain and egg sauce, but the first time a man had ever prepared food for her.

“I was hoping you’d say that,” he replied, his smile containing secrets she wouldn’t decipher until it was too late.

The next morning, she woke to a text from him:

“Good morning, my love with the universe in her eyes. Dream of me?”

She had, and she told him so. What she didn’t tell him was that in the dream, he had been walking away from her, his back turned as she called his name, her voice growing hoarser with each syllable until no sound came out at all.

He knew exactly what she wasn’t and what she was. She was a reserved, well-nurtured girl who would love wholesomely and honestly. She soon began to see them as lifelong partners, like her parents in appearance if not in substance. At 28, she began to attract other suitors, some better, some not, some just there — men who noticed the quiet dignity she carried or the way she listened intently when they spoke.

But her heart was locked away, he holding the only key.

He kept quiet, however, about their future. She was approaching 30, and now the fear of what she grew up with crept in: “Good for nothing, who no man will ever choose.” Her life was wrapped around his, and without a personal vision or purpose for her life, all she desired was to be “Oga’s Wife.”

“Do you ever think about us getting married?” she asked one night as they lay unclad in the darkness of his one-room apartment, the ceiling fan spinning lazily above them, pushing around the hot air rather than cooling it.

“Marriage is just a piece of paper,” he answered, his voice distant. “We’re already committed, aren’t we? What would change?”

Everything, she thought. Everything would change. She would have a name that wasn’t tainted by her father’s disappointment. She would have proof that someone had chosen her, despite her eyes, despite her walk, despite all the flaws she had been taught to believe were unforgivable.

“I suppose,” she said instead, turning away from him so he wouldn’t see the way her face fell, the vulnerability she couldn’t afford to show.

The following week, her mother called.

“Grace” Her voice crackled through the phone, distance and poor connection making her sound older than her fifty-six years. “Your cousin Gift is getting married next month. The invitation says plus one. Are you bringing that your boy?”

“His name is Ibro, Mama.”

“Ibro, then. Are you bringing him? Your father wants to know when you two will formalize things. You’re not getting any younger, and those your eyes won’t keep a man without a ring.”

The familiar sting returned, sharper for its predictability. “I’ll ask him, Mama.”

She never did.

The day she died, it was exactly two months after her birthday. She was in his one-room apartment where they both lived, the walls closing in with each passing year. He was in the bathroom, the sound of the shower running, water hitting the plastic basin with a rhythm that had become the soundtrack to their coexistence.

His iPhone device rang, the screen lighting up on the bed where he had left it. In her curiosity — or perhaps it was intuition, that quiet voice she had been taught to ignore — she peered at the screen of his phone and gazed at the caller display. The call rang again and stopped.

“Ibro,” she called, but apparently he couldn’t hear as the shower continued its steady cadence. She pressed the screen with the first finger of her left hand and slid up when the phone chimed with a message from the caller.

The message introduced a curious sentence, and she couldn’t help but tap to read more.

“Baby, have you told her yet? We can’t keep postponing the wedding. My father is asking questions, and I’ve already put a deposit on the hall. I love you, but this is getting complicated.”

She chuckled in a mixture of anger, shock, and confusion, staring at the phone. That was all she needed to trigger all her childhood trauma. She realized she was approaching 30 without a life purpose, with nothing but him — and now, not even that. The only thought in her mind at that moment was to show him pain, to make him feel a fraction of the devastation that was consuming her.

In a rush of emotion, she dashed to the closet just behind the cupboard and pulled out a blunt machete — the one they kept for cutting down the overgrown weeds outside their window. She took her time, swiping through his messages, discovering conversations with different girls, a gallery of intimacy that had never been meant for her eyes.

There was even a message to his mother: “Mama, I’ll bring Kendra home next weekend. She’s the one I told you about — the banker. Very respectful, from a good family. I think you’ll approve.”

The shower stopped, and the bathroom door opened. He walked out with a towel around his waist, water droplets still clinging to his shoulders like tears she would never shed again.

“Babe?” he said, noticing her strange stance, the phone in one hand, the machete in the other. “What are you doing with my phone?”

“Kendra,” she said, her voice eerily calm. “The banker. Very respectful, from a good family. Is that why you never took me home to your mother? Because of my eyes? Because of how I walk?”

His face changed then, the mask slipping to reveal calculation, not remorse. “Put the knife down, Babe. You’re being crazy right now.”

“Crazy,” she repeated, tasting the word. “My father said I was worthless. My mother called me devil’s seed. And now you — you who told me I was beautiful, who said my eyes held universes — you’re calling me crazy.”

“Gift, please,” he took a step forward, hand outstretched. “Let’s talk about this like adults.”

“Adults?” she laughed, a hollow sound that belonged to someone else. “I gave you five years of my life. I believed you when you said I was enough.”

“You are enough,” he said, but his eyes darted to the door, calculating escape routes. “Just not for me. Not forever.”

In seconds, she descended on his neck with a heavy cut. The machete was blunt, but the weight of the blade against his skin and the force with which she used it tore into his flesh and left a deep cut reaching to his bone. She raised her left hand up — because she is left-handed, another oddity her father had tried to correct — and left him with more cuts in his shoulders and chest.

He screamed and fell to one knee as he bled profusely. This was when her eyes cleared, and she stood fixed to the floor, with the machete still in her left grip.

He held his neck with the little strength he had left, raised his left hand and knee, and quickly took the broken mirror on the table — the same mirror she often used to make up her face, trying to make herself beautiful enough to keep him — and plunged it into her chest, under her left breast, pushing it in and puncturing her heart immediately.

Both lovers lay in the pool of their blood. She gasped for air as bubbles escaped her mouth with blood, her eyes — those too-large eyes that had never been able to see her own worth — fixed on the ceiling.

In her final moments, as darkness crept in from the edges of her vision, a strange peace settled over her. For the first time in her life, she felt no fear, no anxiety about not being enough. In death, at least, she had proven her father wrong. Someone had chosen her, even if only to die by her hand.

When the neighbors came in, alerted by the screams, they found two lovers in the pool of their own blood. One lifeless with a piece of glass in her chest; the other drawing slow breaths in half-nakedness, with torn skin and thick blood spreading across the room like a macabre carpet.

She had sworn to kill for her love. He would probably be dead by now. If so, she had killed for love. If not, she had been killed for love. Whichever way, someone — or both — had killed for love.

And in the end, wasn’t that what she had always wanted? To be loved so much by someone that they would rather die or do something extreme than live without her.

In the silence of that blood-soaked room, no one answered. No one ever would.

Chibzuor is the founder of Association of Creative Writers and Executive Director of PurposeForte.